The Two Worlds of James Michalopoulos: by Wayne Curtis

James Michalopoulos

2022

“It isn’t necessary to imagine the world ending in fire or ice. There are two other possibilities: one is paperwork, and the other is nostalgia.”

— Frank Zappa

At the foot of Elysian Fields, on the edge of the French Quarter, stands a rambling complex of century-old buildings that have been curiously conjoined to comprise the studio of James Michalopoulos. Several former enterprises, including a lumber mill and the former Schoen funeral home (as evidenced by a stray coffin or two) now form one sprawling workspace.

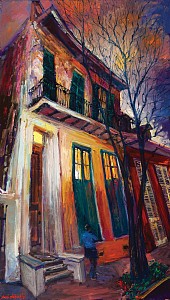

On a recent early evening, a pair of easels sat amid a tenebrous, empty space. One held a partially completed canvas of a three-story corner house viewed from the apex, the house looming and a pair of streets diverging into separate distances. The workspace was surrounded by high-powered utility lights, and where the lights focused it was as bright as the Superdome. The outer margins of the work space were demarcated by drifts of small cardboard boxes that until recently had held tubes of paint. Beyond the drifts, shadows attenuated and became lost in the distant corners and heavy beams.

In this space, Michalopoulos is surrounded by two cities. One, the metropolis of art he has created on canvas, has changed only gradually over the years. The other, the real one just outside the doors, is evolving with disconcerting rapidity.

The canvas city consists of buildings scattered around the studio, leaning against walls, posts, and tables. He has created this city, canvas by canvas, with houses that dance, musicians who don’t produce a note but still are imbued with rhythm and syncopation, and cars that have never seen traffic. The houses entice you to come inside and lose yourself—the musicians invite you to groove and sway, the autos are bulbous and soft and look as comfortable to lean against as an overstuffed Chesterfield.

Michalopoulos paints with a palette knife, creating dense layers that are tactile—even from a distance. Perhaps it’s not surprising that writers and critics also use the verbal equivalent of a palette knife to layer adjectives when describing his work. “His paintings of New Orleans architecture and automobiles are bloated, crooked, skewed, tilted and energetic, sexy, surrealistic, and overindulgent,” wrote Chris Rose in the Times-Picayune in 1994.

Michalopoulos’ route from his upbringing in the Northeast to this studio is at once common and extraordinary. He was born in Pittsburgh, raised in Connecticut, and attended college in Maine. In the 1970s, he managed food cooperatives in the Boston area and launched small-scale businesses selling fruit and fruit juice. While living in Washington, D.C., he gave into restlessness one winter and hitchhiked to New Orleans, a city he’d never visited, with the semi-reptilian thought that it would be good to get out of the cold.

Somewhere along his eclectic career path, he took up sketching and painting as a way to pass his time. During a trip to Niagara Falls, he sold his first work to the owner of a building he had just sketched. “I made—I don’t know—twenty-five bucks for four days’ worth of work,” he said.

Arriving in New Orleans, he had a backpack with a few personal belongings and some art supplies. His last ride dropped him at an exit ramp off I-10 near Elysian Fields late one night, and he walked the last mile into town. The live oaks with gnarled branches grasped toward the colorful houses and people sat amidst the shadows and laughter on their porches. “I’d never seen anything like it,” he said. “It was a great entrance.”

At first Michalopoulos camped out in empty houses, spending his days sketching shoppers waiting for the bus outside of Schwegmann’s Grocery, selling them the drawings for a dollar or two. He started painting portraits of tourists and vernacular architecture, across from Houlihan’s on Bourbon Street. Eventually he upgraded to a $75 a month apartment on Rampart Street.

Gradually, his artwork attracted attention. His shows moved from pizza parlors to galleries. His studio relocated from the street, a move linked to the fact that in the 1980s the city’s streets took a darker turn, as happened elsewhere, with rising crime and a crack epidemic. With money from the sale of his paintings, he started acquiring buildings that no one else wanted—including an old beer warehouse just off a drab, slightly dangerous place called Frenchmen Street. He used it as a place to experiment with color and space—carving out a cockeyed interior of tin, chain link and scavenged planks, where he could both live and paint. His success continued as the end of the millennium approached and then sped past. He bought more property, including his rambling studio space on Elysian Fields.

In many ways, the world he created on canvas changed little. Here were still vivid, polychromatic, century-old houses that swayed to a modern beat, populated by people who ranged through wide emotions—from the unfiltered joy of a street dance to a vaguely rueful Edward-Hopperish introspection. His city was almost always infused by a light that seemed to emanate from the canvas.

Change to this canvas city came only slowly and subtly. For instance, on a recent visit, Michalopoulos told me that he was painting more now from memory. As a result, the houses were slowly becoming more articulated and complicated (Cataclysmica, page 331). Yet the New Orleans of his arrival remained vibrant, strong, and instantly recognizable.

In late 2019, the tranquility of Michalopoulos’ studio on Elysian Fields was disrupted by days of pile driving—a relentless “ker-chunk, ker-chunk” could be heard for blocks and emanated just a few yards from his studio wall.

Construction had begun on a 133-room, four-story Hampton Inn to occupy the site of a former potato chip factory. The design calls for a boxy, bland building that would not be out of place at a freeway exit ramp, save for a handful of balconies applied clumsily like too much makeup.

That’s not the only change taking place nearby. A block away in the other direction a quirky, labyrinthine nursery which specialized in water lilies and other aquatic plants for backyard ponds and fountains. Recently shuttered, it is now slated to become an Airbnb complex.

Across Elysian Fields, a veritable tag sale of adjoining properties, including two sprawling warehouses, recently went on the market—37,000 square feet of interior space plus several lots for $6.9 million. Part of the sale includes the site of a popular nighttime art market on Frenchmen Street, where local artists and craftspeople vend their work to tourists who stop by between sets at nearby nightclubs. With the city’s most music-filled street at the front door, it’s not hard to imagine that, in time, more pile driving will presage something slick, canned and entertainment-districty.

Gentrification was first coined by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964, and it generally refers to long-time residents being forced out by an influx of “the gentry”—relatively well-off newcomers who drive up real estate values. Poor tenants are pushed out by landlords seeking higher rents, as are poor homeowners who can no longer keep up with rising property taxes. This often happens hand in hand with commercial redevelopment, in which longtime businesses shutter and new, better-funded enterprises, including national chains, take their place.

Concerns about gentrification are often anchored to an implicit notion: once upon a time there was stasis and stability, and now that time is rapidly being lost. Of course, cities don’t exist as fixed snapshots; they’re dynamic. They evolve and change constantly, with residents moving in and moving out, and buildings coming down and new ones going up. A city that doesn’t evolve is a dead city. The problem with gentrification comes with the velocity at which this occurs. As Daniel Herriges wrote in Strong Towns, “When the neighborhood is gentrifying rapidly… there’s a very visible difference between who’s moving in and who’s moving out.”

Artists have long been viewed as an indicator species for gentrification. They arrive early in marginal areas with their easels and paints and occupy raw, inexpensive space. Other pioneering bohemians follow behind, which draws the attention of boutiques and coffee shops and chef-owned restaurants. Then come the well-heeled who fix up houses, and real estate developers who buy industrial space and scatter the artists, who are forced to move again to the distant margins and inexpensive space.

Michalopoulos was fortunate enough with his early success as a painter to acquire buildings, including that former beer warehouse-turned-home. Despite home ownership, he could not avoid displacement entirely as he, along with the rest of the neighborhood, could not withstand the noise and disturbance from increasingly popular Frenchmen Street.

A case might be made that Michalopoulos is in part to blame for aiding and abetting rapid neighborhood change. Not because of his property purchases but because he shaped a broader narrative. Forty years of painting modest Creole cottages and shotgun houses had opened a door for the arrival of the gentry. And when they came, they came rushing into the Bywater and the Marigny, wanting to own a piece of classic New Orleans, to own a Michalopoulos house.

It’s not the first time that artists have opened those doors. George Washington Cable’s sentimental stories about the waning days of Creole culture in the 19th-century French Quarter and the writings of Lafcadio Hearn and others served as magnets for well-off visitors who suddenly desired to travel south and see the place for themselves. Their writings laid the groundwork for the revival of the French Quarter, beginning in the early years of the 20th century.

Gentrification hadn’t yet been coined, but the poor Sicilian immigrants, who, among their many contributions to the neighborhood, restored balconies and installed fountains in courtyards, were forced to leave the tenements to make way for richer newcomers from the upper United States. These immigrant families would certainly recognize the concept, if not the word.

More recently, Tulane geographer Richard Campanella has noted that the revitalization of the impoverished Treme neighborhood happened shortly after the success of the HBO series named after the neighborhood. This was part of an influx of post-Katrina newcomers, whom Campanella has written were “self-selected for Orleanophilia, or a fascination with this place and the sense that it’s undiscovered… that’s why there’s a boom on, because there’s a sense that it’s this ‘undiscovered Caribbean Bohemia’”—a notion that at least in part was fabricated by artists in various media.

Starting in the 1980s, the paintings of Michalopoulos surely helped alter America’s perception of a city then reeling from that hollowing-out that resulted from a confluence of factors, including 1960s and 1970s-era white flight, and the crack epidemic wrecking cities nationwide. The houses along the streets may have been suffering from acute neglect, but in his paintings the city was alive and seemed to have in its midst the potential for a far brighter future. The colorful houses seemed to sway calmly under strangely protective night skies, and musicians played like sentinels guarding a besieged culture. As Bradley Sumrall, Curator of the Collection at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, wrote in his forward to this book, “There is perhaps no living artist more deeply tied in the mind of the public to the visual landscape of New Orleans than James Michalopoulos.” Once you’ve been exposed to his work—whether in a gallery, on a Jazz Fest poster, or in a book—it’s hard to walk through a New Orleans neighborhood and see it in the same way again. It’s equally hard not to want to buy into it.

When Michalopoulos started his New Orleans architectural paintings, few houses here were painted the bright Caribbean colors so common now. They tended to be more staid—tans and whites and pale blues. But slowly starting in the mid-90s, houses in the Marigny and then the Bywater and beyond were splashed with the colors of the ribbon counter, with vivid azures, ochre-yellows, and deep burgundies applied to weatherboards and trim. Increasingly colorful neighborhoods brought in more visitors, which led to more buyers, and a narrowing of the gap between reality and Michalopoulos’ imagination. The bright colors were a trip to an exotic land, the compact neighborhoods a trip to a more community-minded past.

The notion of nostalgia began in 1688, when Swiss mercenaries, traveling afar to fight wars, were diagnosed with what was deemed a debilitating and diagnosable medical condition. Symptoms included ennui and long fits of weeping. Even as late as the American Civil War, soldiers far from home were frequently found to have been afflicted with nostalgia. “When this queer disease seizes its victim with a strong grip, he is almost as sure to die as though his malady were cholera,” wrote an observer in 1896.

Nostalgia today is less dire, and considered something of a feral and archaic infirmity. But it surely persists now as more of a philosophical rather than a medical condition. It manifests itself as a melancholy longing for an earlier time, one that may or may not have actually existed.

One needn’t even travel far, like the Swiss mercenaries or Civil War soldiers, to be afflicted. Glenn Albrecht, an Australian philosopher, noticed an upswing in debilitatingly dour moods among his countrymen who hadn’t left home. As the effects of global climate change spread, many felt displaced from their lives as their gardens failed and familiar birds fled in the wake of drought and other unwelcome events. He coined a new term for this specific variety of sadness: solastalgia, which he defined as “a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at home.” It most commonly describes distress arising from natural or manmade environmental change. But it likewise can apply to wholesale cultural change.

Solastalgia isn’t in any medical handbooks, and there’s no agreed-upon set of symptoms. But long-time New Orleanians are certainly suffering from it as widespread change sweeps through neighborhoods long overlooked. This is evidenced by laments about the loss of neighbors, shops, and second line and Mardi Gras Indian culture. The New Orleans that Michalopoulos found upon arrival—of inexpensive French Quarter apartments, affordable houses on the fringes, reclaimable studio space just about everywhere, and the collegial culture it engendered—has been gradually ushered off the stage.

Michalopoulos has been working outside the walls of his studio to mitigate some of that change. Some six years ago, he acquired the Schneider Paper Company building, which, like his Elysian Fields studio, was an agglomeration of haphazard spaces—including a four-story brick building constructed more than a century ago as a brewery. The property, which was dubbed “NoRo” for its location on North Robertson Street, totals some 110,000 square feet, all set next to a constantly rumbling rail-switching yard.

Colorful, careening hallways lead into more than 100 sprawling artist studios, along with a community art gallery. With rents well below market rate, creatives stay for years. Collaborations blossom and many evenings the courtyard beckons impromptu gatherings.

“I’m not here to play,” he told me. “I’m here to do something or leave.”

If Michalopoulos is afflicted with nostalgia, it’s for a time when an artist with a vision could come to New Orleans and find a space from which they could make their way. The idea behind NoRo has been to recreate in a small but meaningful way the New Orleans of four decades ago: a place where someone with a few art supplies and an imperative to create could find an affordable place and pursue a vision. He’s not trying to roll back time, but he’d like to establish a piece of the old city where funk prevailed, where artists had a home. Toward that end, he’s also acquired a large empty lot adjacent to the building complex, where he envisions a community of artists gathering regularly, then inviting in the public.

“I’m going to call it Orleania,” he said. “And it’s going to be an installation art experience. I’m going to art direct. Probably 30 artists will be involved in it. It’s going to be a several-hour experience. You’ll go there and hang out. We’ll have a cafe and drinks, and there will be a nightly show and a bonfire.”

His vision on canvas and his vision in brick and mortar occupy separate but overlapping worlds. One is mostly free and unfettered; the other involves paperwork, regulations, and approvals. True visions can be interrupted, but they never die.

New Orleans’ leading industry has long been its past. No matter how steadily the city moves into the future, it continually looks over its shoulder to admire what came before. In part, that’s good marketing. Tourists perpetually seek out New Orleans’s fabled past. Sidney Bechet tunes spill out of clubs on Frenchmen Street and foodies flock to places to sample dishes their great grandparents would have recognized. New Orleans does not wear the futuristic very easily. A few years ago, a progressive chef touted his molecular fare; his restaurant didn’t last very long.

Nor is the city home to any dramatic, shiny, and modern Gehry-ish building. The few skyscrapers that have been built on these unstable soils are boxy and instantly forgettable. Rather, visitors come to walk the old neighborhoods, filled with those bright, ornate houses. Tourists post to Instagram the spalling plaster walls in the French Quarter, and flickering flames in copper lamps. The deep appeal of these historic neighborhoods has helped fuel a boom in short-term rentals. Why stay in a hotel when you can rent a bedroom in a residential neighborhood and live like a local for a weekend? It’s like borrowing a beautiful vintage coat from a friend.

Maintaining a connection to the past while inexorably moving forward is a complicated endeavor. Historically, nostalgia tends to be most acute during times of wrenching change, such as war or technological revolutions. David Lowenthal, author of The Past is a Foreign Country, writes, “A perpetual staple of nostalgic yearning is the search for a simple and stable past as a refuge from the turbulent and chaotic present.” Think of nostalgia as a complex form of buyer’s remorse. Unsure of where we are, we seek to return to where we were.

With nostalgia, one does not ever leave home to feel adrift, so the remorse may be even greater. For those in such throes, Michalopoulos’ paintings of houses, cars, and musicians may not offer a cure but can alleviate the symptoms. They capture the fabled essence of the city and invite one to return, at least in one’s mind.

Nostalgia may be sepia-toned or vividly colored, determined by your personal memories and leanings. For example, 19th-century British designer William Morris’ nostalgia was in color. He once described his version as “the ancient time of sunflowers.” The world into which Michalopoulos invites the viewer—of a dynamic New Orleans that is at once past and present—is decidedly colorful and induces a sense of warmth and wonder.

A friend told me recently that she experienced his paintings as if they were a dream, a vision in which the perspective wasn’t quite right, with the focus getting wispy around the margins. They capture the fuzzy memory of a place that once was but no longer is, yet still continually captivates and provokes wonder. In the bargain, they help us view the present through a wistful lens.

Albert Einstein once said that either everything is a miracle or nothing is. Michalopoulos’ work offers a way to spend some time in a place where everything is a miracle.

Wayne Curtis

Author and journalist