The Crazy Big, Insanely Colorful, Completely Far-Out Vision of James Michalopoulos

February 1, 2024 - Wayne Curtis, Garden & Gun Magazine, April/May 2019

A staircase has gone missing—it was supposed to be over here, says the artist James Michalopoulos. He had marked the location on the warehouse floor the other day, and those marks had been erased or moved or something happened, and so he scouts around. “Oh, here it is,” he finally says, tapping a scuffed line with his toe where the stairs and their ziggurat landings will soon arise. He demonstrates with his hands how the steps will make their way to the second floor with an erratic determination, making a “pfft…pfft” sound at each pivot of the future staircase. It seems unduly complicated and taxes my imagination.

Nor does his description help us get to the second floor, so he and I scramble up a ladder, rung by rung. From the walkway above, we scan a sort of two-story indoor village of artist studios that Michalopoulos has been constructing within what he calls “the big hangar,” just one part of a sprawling 110,000-square-foot complex he acquired a few years ago. Sited next to a clamorous rail switching yard and a roadway overpass in a charmless section of New Orleans’ Upper Ninth Ward, the building was originally a brewery and then stored paper before it was occupied by artists.

We wander catwalks and narrow walkways that connect the soon-to-be second-floor studios. Walls vector this way and that; windows have been installed without benefit of a level. Obtuse angles abound. It looks like Pee-wee’s office park, assuming that Pee-wee eventually grew up.

Over the past thirty-five-plus years, Michalopoulos’s moody, heavily textured New Orleans streetscapes have made him one of the most recognizable artists in the city. In his fevered imaginings, buildings seem to dance and sway, the upper floors appearing to head in one direction and the ground floors in another. The inanimate seems animate, and it’s all at once enchanting and haunting, like the talking apple trees in The Wizard of Oz. His paintings can forever change the way you see the city, and as such, his work has become almost inescapable—he’s been commissioned to paint six Jazz Fest posters, which is the New Orleans equivalent of getting a bird painting on a duck stamp. Notables such as the actors John Goodman and Sharon Stone have acquired his paintings, as have many corporate collections. In 2017, his work was the subject of a wide-ranging retrospective at the city’s Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

“James is very process driven,” says Bradley Sumrall, the Ogden’s chief curator, who organized the exhibit. “He opens himself up to a city, getting a feel for the place, with the sounds and smells and humidity, and then depicts that quickly on canvas. It’s like a dance. It comes from a very emotional and spiritual place.”

That critical and commercial success opened a door for Michalopoulos to join the entrepreneur class. The old warehouse is just one of his acquisitions over the years—he’s invested in other places in New Orleans and the nearby parishes. He owns a rum distillery, which recently released a new cayenne liqueur, along with houses and galleries. In the process, he’s also become a not-insignificant employer in New Orleans—up to, at times, ninety full-time and contract workers keep the cogs of various ventures in motion.

Nonetheless, he’s remained something of a cipher in the city he calls home. He rarely does interviews or offers up pronouncements at public events. He’s kept his studio and other projects largely out of the public eye. “I’ve let the work do the talking,” he says. What’s more, some of his political ideas are “outside the range of normal,” he admits, “so in the interest of harmony, I don’t bring them up.” Now he’s feeling a bit more chatty. At age sixty-seven, Michalopoulos has emerged as a force in New Orleans, a cheerleader and community builder for the creative class that for so long has helped make the city the wonderfully idiosyncratic place that it is—one in danger of succumbing to the rent hikes of gentrification. These artist studios are just the next step.

We leave the upstairs the same way we arrived, down a ladder. Watching him descend amid wonky walls and walkways, it looks for a moment as if he’s climbing out of one of his own paintings.

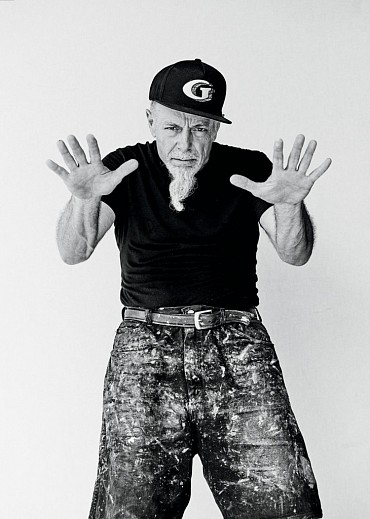

Michalopoulos has been painting professionally in New Orleans for more than half of his life. He’s wiry and compact, with a Ho Chi Minh beard in front and a Karl Lagerfeld ponytail in back. He moves with easy and economical motions, like someone twenty years younger, making him something of a walking advertisement for the yoga and meditation he practices regularly. And he seems utterly at home in the city—when we biked across the Marigny from his studio to the old paper warehouse, he pedaled like a local, which is to say without a helmet and with scant regard for traffic conventions.

Yet he’s actually a child of the Northeast—born in Pittsburgh to a Greek immigrant father, raised in Connecticut, college in Maine, work in Boston. His early résumé reads like the 1970s writ small: He managed a Boston food co-op and helped found another in Cambridge, then launched some small businesses (Fruit Juice on the Loose and Magical Melon Mobile). He considered returning to school for a PhD in economics or engineering.

Then one day he picked up a pad and pencil and started drawing, largely out of boredom. (“I just had the idea it would be a good pastime,” he says.) Art had been “in the air,” however, when he was growing up. His father, James Anastasiou Mitchell, a noted architect in Pittsburgh in the 1940s and ’50s, codesigned the city’s technologically innovative civic arena, and was later credited with putting the first urban park atop a parking garage. (His son reclaimed his father’s Greek birth name for himself.) Michalopoulos’s uncle was the abstract expressionist painter William Baziotes, whose work hung in his family’s house, as did that of other famous artists. “My dad was an art collector—Georges Braque, Picasso,” he says. “I didn’t understand it, necessarily, as a kid. But I was like, yeah, this is fanciful and this is what a person can do. I was quite influenced by it.”

During a vacation in Niagara Falls, New York, in 1977 he spent a few days sketching an intriguing stone building. One day the building’s owner, an architect, came out, took a look, and asked to buy it. “I made—I don’t know—twenty-five bucks for four days’ worth of work,” Michalopoulos says. “But I was off and running.”

He moved to Washington, D.C., and in 1978 hitchhiked to New Orleans, where he’d never been, driven by a vaguely reptilian imperative to get away from the cold. He brought a backpack, his portfolio, and a notion that the city was both “warm and exotic.” His final ride let him off on upper Elysian Fields, from which he walked the last mile into the French Quarter.

“I’d never seen anything like it,” he says of the broad, leafy boulevard. “All those wonderful houses and lush trees reaching out. And people were hanging out at ten o’clock at night. There was a vitality that was immediately evident to me. It was a great entrance.”

He spent the winter painting on the streets, selling what he could before hitching back north. The next winter, he ventured to Key West, Florida, but it didn’t take. He returned to New Orleans the following winter and basically never left.

Those first years were hardscrabble. He would set up at high-traffic locations, like the Schwegmann grocery store. “While people waited for the streetcar or taxi, I’d nail ’em and then try to hustle them with a sketch,” he says. He did courtroom drawings for a television station. For stretches he lived a hermit-crab life, squatting where he could, and at one point was joined by two fugitives from New York. “Then one of them stole everything, except for my portfolio,” he says. “Which gives you an estimation of the value of my art at the time.”

His art improved, and his prospects brightened. People started to notice his work and seek him out. Within a decade of his arrival, he was specializing in architectural drawings, and his style began to evolve into his now-iconic aesthetic. Writers describing his work used such terms as “expressionistic,” “impressionist-like,” and “almost psychedelically distorted.”

“When I walk down a street in the Marigny or the Quarter or Uptown, there’s this magnificent visual drama that, along with the light, makes for a perfectly magical world at moments,” Michalopoulos says. “It’s all a terrific source of variety and virility and fecundity. I don’t think I would run out of material here for another three or four thousand years.”

His street scenes were familiar, yet somehow not, like New Orleans seen through an antique wavy glass pane. “For me the number-one obligation is to make something that’s alive and interesting,” he says. His is a city with the evening skies of Goya, the animated houses of Dalí, and the thick impasto complexity of Van Gogh. “It’s a city on the move,” he says. “There’s a kind of diaphanous quality to what I observe, where things are a lot less solid than they seem to be.”

In his essay accompanying Michalopoulos’s 2017 exhibit, Sumrall, the Ogden curator, explains the artist’s appeal: “By immersing himself in the moment—light slanting through thick humid air, leaning buildings drenched in Caribbean color, the heady smell of sweet white flowers and urban decay, the sound of a distant brass band—he arrives at an emotional understanding of the scene. The result is a painting that we feel before we analyze, a painting that is more spirit than structure.”

The style resonated—the ten-dollar bills Michalopoulos was fetching turned into hundreds, then more. He upgraded from his seventy-five-dollar-a-month Rampart Street apartment. When the opportunity arose, he started to buy run-down buildings, including a former beer keg warehouse a half block off Frenchmen Street that had insulated cork floors and gaping holes in the roof. He secured it with a down payment of a dozen or so paintings, and that building became a blank canvas for him, a home where he could experiment with deconstructed interiors, crafting irregular walls of corrugated fiberglass and chain-link fencing. He lived there with his then girlfriend and their daughter and her two boys for years, until the rising clamor of Frenchmen Street drove them out.

A two-minute walk away on Elysian Fields he also bought what would become his studio, another complex of buildings, haphazardly conjoined. (One of these buildings was a funeral home; some caskets linger behind.) These days his easel is set up amid wooden joists, brick walls, and errant rays of sunlight probing through gaps, which give an idea of just how large the space is. This work area exists as a sort of island in the dark, rimmed by a shoreline of empty white boxes that once held tubes of paint—he applies the oils thickly with a palette knife, going through them like a confectioner through sugar. A slightly spattered large-screen television sits propped on another easel, vertically. He’ll sometimes start a painting by looking at a photograph on-screen, he says, then will switch off the image and let his imagination go. But most scenes emerge wholly from his mind. “When I work from imagination, they tend to be more simplified, more colorful,” he says.

The studio complex has served additional purposes—his ex operated an alternative theater there, the side yard has been a sculpture garden, and Mardi Gras krewes have held late-night bacchanals there. All the while, the neighborhood has gone from neglected to desirable. A chain hotel is slated to go up next door, with initial plans calling for a bland stucco box—something that could just as well be moved by barge from an interstate interchange. (The neighborhood has been pushing for better design.)

Michalopoulos sees these kinds of changes as red flags—harbingers that what has long made New Orleans unique is not guaranteed to last. “I’m afraid that, like Manhattan, it will become inhospitable to creatives,” he says. “Our commitment is to doing our part to mitigate that change and preserve that culture.”

So his Elysian Fields studio will soon enter its next phase: Michalopoulos plans to convert part of it into a destination he hopes will add character to the neighborhood. The complex will include a bistro with an offbeat courtyard he’s designing, and his boutique Hotel Lux Galactica. He envisions a raggedy tower eventually rising above it all—he uses the word dystopian to describe his vision, an edifice bristling with unconventional geometries and colors. The tower will inspire wonder and—not incidentally—serve as a silent scold to the drab architecture proposed for next door.

“We’re one of ten places that really move the needle on the planet,” he says of New Orleans. “We treat very casually the wealth [of culture] we have. This reminds me of people not appreciating their health until they lose it. It’s a wake-up call.” Looking toward where he hopes his tower will one day rise, he muses a bit. “I can’t wait,” he says. “It will be this jagged, frigging freaky thing going up in the sky,” he says. “And it will say, we’re in the right place on this planet.”

Discussion of Michalopoulos’s forthcoming hotel, along with his other high-visibility design projects, invariably leads to the subject of gentrification, and when that comes up, he lets out a plaintive sigh. Michalopoulos has arguably been both an agent and a beneficiary of gentrification. (Only a terminally melancholy person would look at one of his streetscapes and not harbor dreams of moving to New Orleans.) He sees both the upside and the downside. With the city’s changing economics and problems with drugs, he watched as New Orleans hollowed out in the 1980s and ’90s. “There were literally hundreds of abandoned homes,” he says. “And so I take heart that they have been reinhabited, and that many of them have been saved that would have fallen into oblivion.”

Yet, he acknowledges, the area around his studio is “a much more expensive neighborhood. The class composition has changed, and it’s not as hospitable for artists. I don’t measure everything in the world by that yardstick, but for the arts community, it’s much less viable as a neighborhood.”

Bit by bit he’s been trying to create an environment where artists and other creative types have a place to work—including at this new studio complex, where he’s committed to keeping rents low, since the city’s stock of once-cheap industrial space is shrinking. He also has plans under way to create inexpensive housing for artists. Near the warehouse, he’s acquiring a city lot where he hopes to raise around fifty housing units that would be “affordable and ecologically and socially responsible.” He’s looking at other locations in the neighborhood for similar projects and has drafted plans for an artistic community, a little more than an hour north.

“It’s about creating a safe harbor for expression,” he says. “The city was always an inexpensive place to live, and it’s turned into an expensive place to live. Honestly, it’s not just artists that are in trouble, it’s society in general. It’s less and less practical to own one of these little New Orleans houses, and in some cases impossible. So we build community. This is a culture of celebration and personal expression, and we think that safe, predictable housing supports that. I think that’s important to leave to New Orleans.”

He admits these efforts are a finger-in-the-dike approach, and not game changers. But ultimately, he’d like to help revolutionize housing the way Henry Ford did auto production. He’s brought in a few folks to research and brainstorm how to make housing components affordably using new technology like 3-D printing. “What we need is a breakthrough,” he says. Income is stagnant in New Orleans, and land prices are rising—that leaves construction as the only area where costs can be dramatically reduced. “The technology is not quite mature, but it’s getting very close,” he says. “A thousand errors and then you get it right.”

Michalopoulos beckons me over to one of the old brewery’s large, grimy windows. Outside, traffic limps up a ramp over the rail yard. Beyond the elevated roadway, he’s acquired another property—a full city block, edged on one side with trees and dotted with concrete slabs. “I’m going to call it Orleania,” he says. In a perfect world, he imagines designing a space there for art installations and a café and performances. “There’s a tendency among a lot of people to tend toward refinement,” he says. “I would like to funkify that.”

The goal? “You would come and hang out, have a café and drinks, and there would be a show,” he says. “It would be a bit of Cirque du Soleil, and a bit like New Orleans culture.” He envisions a place for artists and like-minded others to gather and enjoy the world around them—just as he did when he arrived in New Orleans decades ago, when cafés and bars and parks served as extended living rooms for people who may have lacked resources but had a surplus of creativity.

As he sketches out his dream of a village of art, food, and simple pleasures, a long line of trains next door starts the coupling and decoupling, sending a cacophonous, cascading thunder rolling through the building. Michalopoulos doesn’t seem to notice, but he continues on, pointing out passengers in cars on the overpass, and imagining them peering down and wondering what the hell is going on down in Orleania.

“You want some creativity? Take away the answers and leave people alone to develop their own answers,” he says, summarizing his approach to life. “You want uniqueness? It’s found not by searching for it on the internet. It’s by shutting your internet down and figuring out how to fix that thing yourself.”

Back to Press